Recently, a 2024 NOAA blog outlined the growing rate of billion-dollar environmental disasters and the significant cumulative cost— $1.2T over the preceding 10 years. As global temperatures continue to rise, several industries are taking steps to abate the worst-case scenarios. However, efforts to mitigate the worst impacts through decarbonization of the built environment need to be supplemented with efforts towards increased adaptability and resilience to the changing climate.

In general, building codes and building design and construction focus on resilience from some of the most common and destructive hazards (outside temperatures, fire, and seismic activity); however, there is an emergent need for building design and construction to be responsive and adaptive to an even broader range of environmental hazards and conditions. Such hazards include: increasingly extreme temperature conditions, more frequent extreme weather events, and more frequent utility grid disruptions.

Image courtesy of NOAA

Image courtesy of NOAA

Resilient codes and standards can help bring consistency and scale adoption of best practice approaches to building design and construction based on local and regional priorities and changing environmental conditions.

The draft publication of the Connecticut Climate Resilient Energy Code (CT-CRE Code) provides one framework for stakeholders to recognize the benefits of resilient design and scale its development through a standardized code.

What is the CT-CRE Code Framework?

The NBI-authored CRE Code is the product of work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy under the Building Technologies Office. This multi-year effort is led by Clean Energy Group.

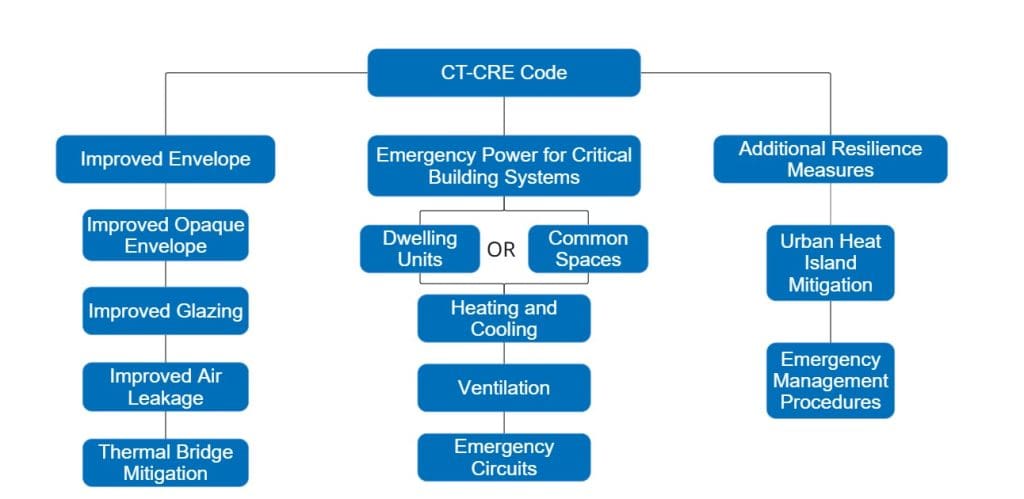

The CT-CRE code is intended to cover the necessary steps for installing climate-resilient energy systems, including efficient heating, cooling, and ventilation. This code also covers on-site renewable emergency power systems that maintain living conditions and power essential services for multifamily affordable housing residents sheltering in place during grid outages.

More specifically, since thermal resilience has been recognized as an inherent benefit of energy efficiency and high-performance building codes and standards for at least two decades, the code includes provisions for such passive design improvements. These improvements include optimized opaque envelope and glazing systems. It also sets criteria for where to provide active heating, cooling, and ventilation systems with emergency power and what types of specialized controls are needed.

For active systems and emergency power, the code allows compliance through a dwelling unit or common space pathway, both of which use “cool/warm room” approaches. In these pathways, active heating and cooling, ventilation, and emergency circuits are provided in certain spaces within the building rather than providing emergency power to the entire building. This approach helps optimize the sizing and cost of emergency power systems.

Image courtesy of New Buildings Institute

Image courtesy of New Buildings Institute

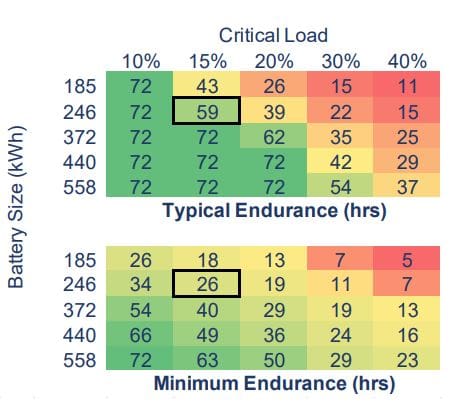

What Methods Were Used to Create the CT-CRE Code?

The project team’s microgrid consultant, American Microgrid Solutions, conducted feasibility and cost studies evaluating different solar + storage system designs for a mid-rise prototype building in the context of baseline and CT-CRE code contexts. These feasibility studies helped identify right-sized system configurations that can provide emergency power to the critical systems for a minimum of 24-hours during an extreme heat or cold event, while also having a positive net present value over the system’s life. These results help establish a baseline for on-site solar and storage requirements to meet minimum capacity needs during extreme weather events.

Image courtesy of Clean Energy Group and American Microgrid Solutions

Image courtesy of Clean Energy Group and American Microgrid Solutions

Other Components of the CT-CRE Code

Cost Effectiveness

Traditional cost-effectiveness methodologies used to evaluate measure proposals for the IECC and ASHRAE 90.1 energy codes compare the first costs of energy measures to lifecycle operational energy cost savings. While the recent inclusion of the social cost of carbon at ASHRAE 90.1 offers a framework for how cost-effectiveness can be expanded to consider additional code measure benefits in cost-effectiveness evaluations, the social cost of carbon alone does not capture the full range of non-energy and non-carbon benefits that resilient design can yield, including those related to life-safety, non-energy economics, grid reliability, and public health. While comprehensively identifying, comparing, and valuing the monetary and non-monetary benefits of resilient design and construction is challenging, it is necessary for justifying and scaling broader adoption of resilient strategies for buildings and the built environment.

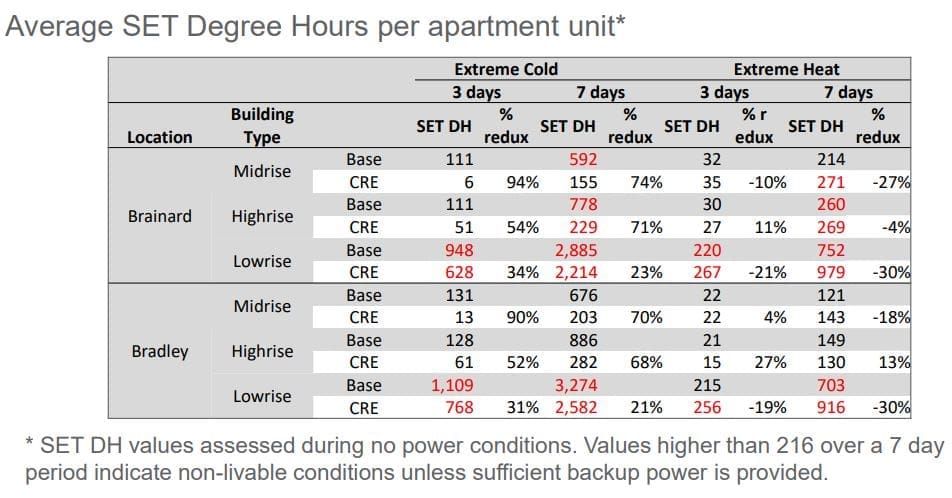

Metrics for Resilience

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) was another integral member of the CRE Code Development project and helped develop the Impact Assessment Methodology and identify resilience valuation metrics. The primary metric for evaluation of the passive thermal resilience of the project was Standard Effective Temperature (SET) degree hours. SET is a temperature metric that accounts for indoor dry-bulb temperature, relative humidity, mean surface radiant temperature, and air velocity. SET degree hours indicate the number of hours that the indoor temperature is a certain amount of degrees above or below a specified indoor comfort threshold. In this case <54°F was used for heating and >86°F for cooling, e based off a LEED pilot credit for passive survivability.

Image courtesy of Clean Energy Group with Data from Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Image courtesy of Clean Energy Group with Data from Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

The initial impact analysis performed by PNNL for the CT-CRE code indicated a significant reduction in SET degree hours for the simulated extreme cold grid outage scenario, with some increase in SET degree hours for the simulated extreme heat grid outage scenario. This increase was most pronounced in the low-rise prototype, which saw a 30% increase in SET degree hours during the extreme heat event. Further analysis leading up to the final impact assessment will review options for mitigating the increase in SET degree hours during the heat event and will establish and evaluate the code against additional metrics related to energy performance, non-energy performance, health and well-being, and economic impacts.

The Future: Standardizing Metrics for Resilient Code Development

As building codes and standards continue to evolve and address the growing climate crisis, they must continue to incorporate resilience-focused requirements. At this point, there is a clear need for consistent use of metrics for evaluating and comparing the costs and benefits of code measures to each other and across projects and climate zones. These metrics will allow for more research into and comprehensive accounting of the full range of benefits attributable to resilient design and construction.

Code development efforts like the CT-CRE code project can advance technical and economic justification of the incremental first costs of resilience measures and allow for a weighting and comparison of resilience measures to prioritize investments in resilient design and construction. Metrics should be established for impact categories such as energy performance, non-energy performance, and health and well-being. They should be paired for analysis with resilience and hazard categories like extreme heat, extreme cold, wildfire, and grid outages.

Through our resilience work, NBI is engaged in establishing consistency in the use of metrics for resilience code measure evaluation and advancing the use of these metrics within and across projects and regions to facilitate decision-making and prioritization around resilient design and construction.

Read more about what our team is working on here.

Authors

Co-authored by Tristan Grant, Associate Director of Codes and Policy, New Buildings Institute

Bio

Co-authored by Kevin Berry, Senior Climate Advisor, New Buildings Institute

Co-authored by Kevin Berry, Senior Climate Advisor, New Buildings Institute

Co-authored by Ariel Brenner, Project Manager, New Buildings Institute

Co-authored by Ariel Brenner, Project Manager, New Buildings Institute

Did you enjoy this content? Consider supporting NBI’s work with a donation today.