This blog was originally published as an article in Facility Executive on October 9, 2018.

As the extreme weather impacts of a changing climate become more urgent, cities and states are racing to put in place strategies that will reduce carbon emissions, including driving down the energy demand from local building stock. Buildings account for 40% of carbon emitted in the United States, and up to 80% of emissions in cities. Policymakers understand that addressing the building sector is essential to meet energy and climate action goals.

For new construction, advanced energy codes are emerging as the go-to option for achieving high levels of efficiency. By planning for increasing stringency over a number of code development cycles, jurisdictions can impact 100% of all newly constructed buildings. But what about the vast square footage of all buildings that are already constructed and occupied? New policies are being explored to trigger energy efficiency upgrades in poor performing buildings as well as utility programs to financially incent and support such improvements.

For new construction, advanced energy codes are emerging as the go-to option for achieving high levels of efficiency. By planning for increasing stringency over a number of code development cycles, jurisdictions can impact 100% of all newly constructed buildings. But what about the vast square footage of all buildings that are already constructed and occupied? New policies are being explored to trigger energy efficiency upgrades in poor performing buildings as well as utility programs to financially incent and support such improvements.

A growing number of cities and states are leveraging local utility incentives to offer programs to building owners, and one example is RepowerPVD in Providence, RI. This is a voluntary energy challenge program that connects participants with efficiency rebates from National Grid for energy upgrades. It is designed to help large buildings located in the city commit to either achieving a 20% reduction in energy use by 2025, or “Race to Zero” to become the first zero energy (or ZE) building in Providence.

Zero energy buildings are those that achieve ultra-low energy demand and meet that demand through on-site renewable energy resources, predominantly solar panels, over the course of a year.

As up to 50% of a building’s energy performance outcome lies in the hands of the operator and occupants, facilities teams are being called on to take the front line in a push to change the approach to energy operations and management of buildings. Leading companies have already seen positive results.

Suncoast Credit Union, the largest in Florida with 700,000 members, has been pursuing sustainability practices for nearly a decade with more recent attention to building energy performance including development of six zero energy bank branches. “In 2013, we started looking at what could be done to save energy with our buildings,” says Bakari C. Kennedy, director of facilities, energy efficiency engineer, and sustainability specialist for Suncoast. The ensuing work included lighting upgrades, installation of hybrid HVAC systems, advanced metering systems, and solar retrofits.

Of Suncoast’s 65 branches, nearly 95% of its portfolio of buildings have some measures to save energy, with the first wholly solar-powered branch opening in Fort Meyers in 2013. In all, 13 of those buildings have installed solar arrays. Branches typically save about $1,500 dollars per month on electric bills over conventional design and operations—totaling about $300,000 annually. The return on these investments is somewhere between seven to 10 years depending on the actual property and the systems installed, Kennedy says.

Setting Energy Use Targets

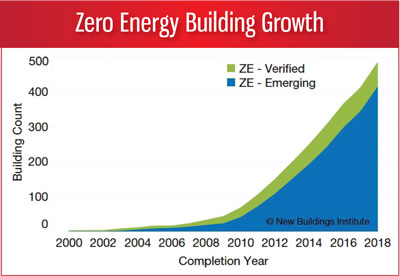

The targets for delivering energy efficient buildings are becoming clear. Lower energy use intensities (EUIs) in buildings result in lower energy demand which means less carbon emitted. New Buildings Institute (NBI) manages a large database of building energy performance data for various commercial building sectors across the U.S. and Canada. Analysis helps researchers understand where EUI targets to achieve ultra-low energy performance by building type could be reasonably set. These include targets for both new and existing buildings in the various climate zones. In NBI’s data set, zero energy buildings are gaining momentum, showing 700% growth in numbers since 2012 (see chart).

Median EUIs for zero energy buildings fall between 15 and 30, but lower numbers are being achieved. Verified zero energy buildings (those that have provided energy use and production data to NBI for validation) have a median EUI of 18. Emerging zero energy projects (those striving for zero energy but are not yet achieving this goal) have a median EUI of 24. Ultimately, the analysis is clear: zero energy performance is feasible in most building types, in all climate zones for both new and existing projects.

Median EUIs for zero energy buildings fall between 15 and 30, but lower numbers are being achieved. Verified zero energy buildings (those that have provided energy use and production data to NBI for validation) have a median EUI of 18. Emerging zero energy projects (those striving for zero energy but are not yet achieving this goal) have a median EUI of 24. Ultimately, the analysis is clear: zero energy performance is feasible in most building types, in all climate zones for both new and existing projects.

In addition to setting targets, facilities teams must understand where they are starting from. Tools are available to help benchmark building energy performance. Most common is Energy Star Portfolio Manager, which can help inventory, track, and communicate the energy use associated with a building or a portfolio. It is also the preferred platform for about 40 cities, counties, and states that have adopted mandatory benchmarking and disclosure ordinances.

Buildings Are Getting Smarter, So Must We

Facilities staff have a number of proven options to help drive down the energy use in buildings, but savvy facility executives will take the first step of planning for continuing education for managers and technicians. The evolution of buildings incorporating advanced systems, highly integrated controls, and on-site distributed generation resources such as solar is growing and driving a dramatic leap in the skills needed to operate and maintain equipment.

These two aspects were spotlighted in a 2015 study released by CABA (Continental Automated Buildings Association) called “Zero Net Energy Building Controls.” The study describes: 1) the Internet of Things (IoT) and 2) Distributed Generation, whereby the building operator ensures not only the building’s operational energy use but also the generation and distribution of energy back to the grid. This is a whole new world of “zero” in the hands of the operator.

“The dialogue on advanced education must change from the burden of the costs of getting operators training and resources to the cost of not getting them,” says NBI research director, Cathy Higgins. “A building that lacks a strong and supported operator is a building that will have tenant complaints, reduced leasing, higher operating costs, and lower asset value and ultimately fail to meet new performance-based policies and carbon accounting that are under consideration. Giving operators the elevated recognition and tools they need and deserve today will increase real estate value for tomorrow,” she says.

While it’s true that achieving zero energy in renovations of existing buildings is more difficult than in new construction, deep energy retrofits to zero energy are attainable. For standard efficiency upgrades, simple diagnostic tools or full-scale audits can help direct facilities staff on where to focus or prioritize buildings in a portfolio. To achieve zero energy-level EUIs, a more integrated approach is required.

While zero energy may be a lofty goal, the progression of “getting to zero” is just as valuable and allows teams to set reasonable goals. Each successful project serves as a model for others, and NBI publishes case studies and provides an annual zero energy buildings list to help owners, designers, and facilities teams understand the “getting to zero” energy pathway.

by Alexi Miller, Senior Project Manager