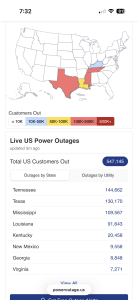

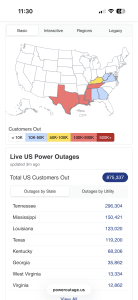

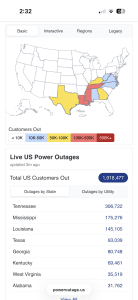

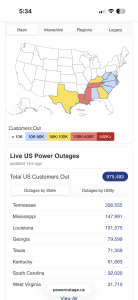

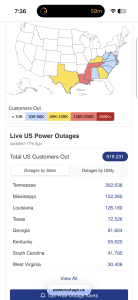

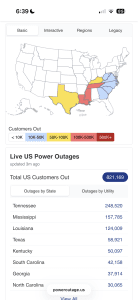

Beginning on Saturday, January 24, 2026, a major winter storm struck several regions of the country, impacting nearly half of the U.S. population. Like many others, I closely followed the forecasts starting Thursday, worrying about potential power outages and their cascading impacts. By Saturday evening, reports of service disruptions, emergency responses, and distress among households and communities began to emerge. I repeatedly checked the power outage map and was shocked by the scale of the impact. The screenshots below show how power outages intensified as the winter storm moved across the country.

|

Sun, Jan. 25, 7:30 a.m. ET – 547,145 |

Sun, Jan. 25, 11:30 a.m. ET – 875,337 |

Sun, Jan. 25, 2:30 p.m. ET – 1,018,477 |

|

Sun, Jan. 25, 5:30 p.m. ET – 975,483 |

Sun, Jan. 25, 7:30 p.m. ET – 919,231 |

Mon, Jan. 26, 6:30 a.m. ET – 821,169 |

Moments like this remind us that energy resilience is not an abstract concept or a niche policy issue. It’s about whether daily life can continue—safely, affordably, and with dignity—when the grid is stressed.

What Energy Resilience Really Means

When we talk about resilience, the focus is often on critical infrastructure: hospitals, emergency services, data centers, and water systems. Those are essential, and they deserve attention. But resilience also matters at the household level.

Energy resilience is about:

- Keeping homes comfortable during extreme cold temperatures

- Ensuring families can communicate, cook, and charge devices, including life-saving medical equipment

- Allowing people to work remotely, care for loved ones, and stay informed

- Preventing avoidable health and safety risks, especially for vulnerable populations

Energy resilience is about maintaining everyday life during disruptions, not just surviving a crisis. When outages occur, the impacts cascade quickly. When heating or cooling systems fail, hot water stops running, food spoils, and access to information disappears. For households already facing high energy bills—often because they live in inefficient buildings—these disruptions are more than inconvenient. Living in buildings that do not provide adequate protection can be dangerous, especially for individuals with disabilities and their caretakers. Around 14.5 million households have medical devices that require electricity to operate; more than 30 million households include at least one person with a disability. Over 29 million Americans with diagnosed diabetes depend on reliable refrigeration to store insulin safely. In 2023, nearly 30% of these households reported experiencing a power outage in the previous 12 months.

Resilience Starts with Buildings

Resilience planning has traditionally been addressed at the system level—focused on hardening the energy system and other lifeline infrastructure. This is an essential step, but top-down strategies alone are insufficient. We also need building-level solutions that protect people and communities while power grid upgrades are underway, which are often slow, massive, and costly. Resilient, energy-efficient buildings reduce pressure on the broader energy system during extreme events because they use less energy than their traditional counterparts, thereby allowing a less-stressed energy system to benefit everyone. Redundancy and avoiding single points of failure are core principles of resilience, and distributed, building-level solutions are a critical part of that strategy.

Buildings that are built to be resilient:

- Have well-insulated walls, roofs, and windows that maintain safe indoor temperatures for longer periods during outages

- Minimize air leakage and use balanced energy recovery ventilation systems

- Use high-efficiency appliances that require less power and are easier to run on backup energy

- Include high-efficiency, variable-speed heating and cooling systems that can operate at low power levels when using backup power

- Have local generation or energy storage to keep essential functions running

These features not only buy time when the grid fails but also lower household energy costs year-round by improving overall energy efficiency. Resilience measures can increase demand flexibility, helping prevent outages and speeding up power restoration by reducing grid stress during extreme heat or cold. They also reduce the need for expensive peak demand power plants.

Resilience Can’t be a Luxury—It Requires Codes

While individual actions and voluntary programs matter, resilient building design will not happen at scale without building codes. Codes ensure that safety and resilience are not limited to those who are best informed or can demand these solutions, but are built into homes and buildings across communities—codes help make safety the default. Currently, energy resilience is treated as an add-on or best practice in building codes. Embedding resilience in energy codes is a critical step.

All technologies mentioned above are commercially available and proven, but they are often considered too costly because they have historically been delivered at a small scale with customized designs. It is most cost-effective and expedient to approach efficiency, demand flexibility, and resilience as an integrated system. Addressing them separately adds complexity and fails to fully leverage incentives and resources that are often offered in silos or piecemeal. Energy codes can help standardize implementation and enable economies of scale, making these solutions not only more accessible but also more affordable.

NBI is leading the effort to embed resilience and demand flexibility in building codes that have traditionally focused on energy efficiency. We helped develop the Connecticut Climate Resilient Energy Code, which outlines standards for climate-resilient energy systems, including efficient heating, cooling, ventilation, and on-site renewable emergency power systems to maintain safe indoor conditions and power essential services during grid outages

In partnership with the City of Tucson, we launched the Resilient Southwest Building Code Collaborative to give communities across the Southwest more options for safe, comfortable, and efficient homes and buildings tailored to their unique needs and challenges.

We have been working with school districts to test emerging EV charging technologies and use electric school buses as “batteries on wheels,” providing backup power to keep essential school and community services running during significant grid disruptions. With our partners, and drawing on our knowledge and field experience, we have also developed guidelines such as Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment (EVSE) permitting and inspection guidelines. In addition, we have developed and submitted code proposals that include provisions for smart electric panels, demand response and load management technologies, and EV infrastructure readiness and charging management systems, supporting both everyday energy use and resilience outcomes. In integrated arrangements like this, buildings can act as nodes in networks of resilient technologies, forming a broader resilient network with the grid.

Drawing on our years of experience, we helped develop and draft resilience provisions to be integrated into ASHRAE 189. Next week we are presenting research on how energy resilience in codes benefits buildings occupants—and the grid—during extreme weather at the 2026 ASHRAE Winter Conference.

These codes and research are important first steps to standardize resilience approaches across regions, help justify initial resilience-related costs, and increase adoption of resilient design and construction practices.

The Time to Prepare is Now

As extreme weather becomes more frequent and severe, we can no longer rely on voluntary measures or post-disaster responses alone. Energy resilience shouldn’t be a luxury or an emergency-only solution. It should be embedded into how we design buildings, set codes, plan infrastructure, and support communities—so that extreme weather doesn’t automatically translate into hardship—or fear.

Resilience has measurable benefits to energy performance, occupant health, and grid reliability. Integrating it into energy codes is one of the most effective ways to protect people, communities, and the systems we depend on—before the next storm hits.

If resilience matters to you and your community, share this article with your network. Stay updated on our resilience work by following us on LinkedIn and signing up to receive our newsletter.

Author

by Nora Wang Esram, CEO, New Buildings Institute

by Nora Wang Esram, CEO, New Buildings Institute

Photo at top: Dennis Zhang on Unsplash