On January 15, 2026, NBI issued a correction that addressed updates to the criteria pollutant intensity factors for fuel combustion.

Expanded Role of Energy Codes

Since their emergence in the aftermath of the 1970s energy crisis, energy codes have primarily focused on energy efficiency, energy conservation, and consumer energy cost reduction. The development and advancement of energy codes over time have focused on cost-effectiveness. (i.e. offsetting the upfront costs of technology and design improvements with reduced operational energy costs). Cost effectiveness is a key metric that policymakers use for evaluating code requirements, so being able to quantify costs associated with broader impacts of building design and operation can help make the case for advanced energy codes. Some jurisdictions do look at the broader economic impacts of energy codes, but these are typically limited to cost savings associated with climate change mitigation, not air pollution. Costs associated with health risks from other pollutants emitted when burning fossil fuels aren’t usually included when looking at outcomes from energy codes.

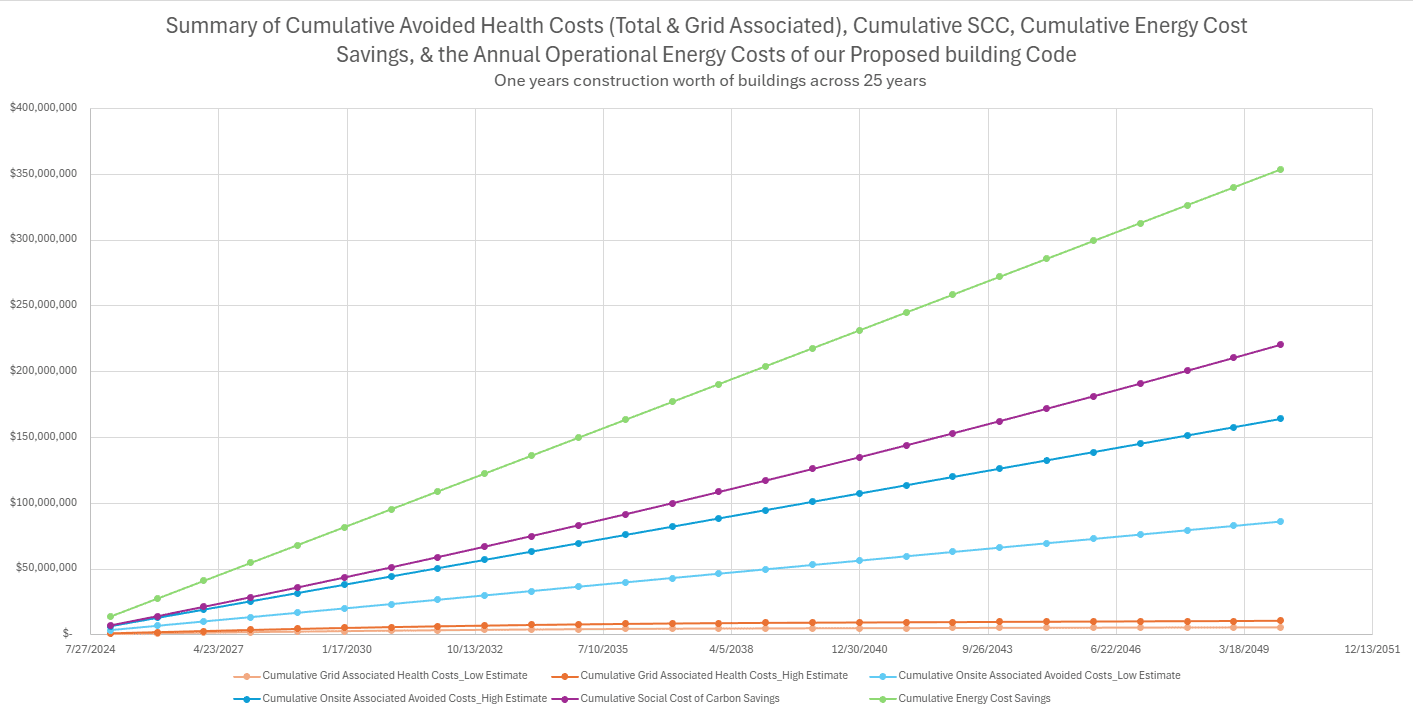

In our recently published ASHRAE paper, Zero Carbon New-Construction Codes: Impacts on Criteria Pollutants in New York, NBI staff used this lens to examine connections between energy codes and health costs by comparing potential outcomes of two different code scenarios (baseline model code adoption and an advanced zero emissions energy code adoption). We found that New York’s annual health cost savings associated with the advanced energy code were not insignificant when compared to the annual energy cost savings, with low–end health cost savings estimates at 24% to 46% of the energy cost and 38% to 72% of the social cost of carbon savings respectively. These findings indicate that energy and construction codes can have a direct and significant impact on health outcomes. Reducing on-site fossil fuel combustion improves regional air quality and people’s health, and these cost savings should be considered when evaluating the cost effectiveness of specific energy codes.

New York Climate Policy and Social Cost of Carbon

New York State has been a leader in climate policy and action, passing legislation that directs the state to reduce emissions, and providing legal and procedural instruments for incorporating climate considerations into state decision making processes.

New York State’s Commissioner Policy #49 in 2010 established several climate goals for State entities including the State’s 85% GHG reduction target by 2050, annual carbon reporting, and establishing of a statewide value of carbon for use by State entities. New York’s Climate Action Council Plan (CACP) of 2022 set the stage for applying these requirements to building code by requiring that “…the state’s building sector should adopt building codes for ‘residential and commercial buildings to be built to a zero-emission and highly efficient standard…’”. Following that, the Energy Conservation Construction Code of New York State (ECCCNYS) has been seen and used as a driving policy mechanism for advancing decarbonization through efficient design and construction. Around the same time, New York’s Advanced Energy Code Act of 2022 established that the code council shall consider:

- Whether the life-cycle costs for a building will be recovered through savings in energy costs over the design life of the building under a life-cycle cost analysis.

- Secondary or societal effects, such as reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

This language provided a policy directive for considering the social cost of carbon in energy code cost effectiveness. The establishment of a social cost of carbon is a damages-based approach that involves identifying and evaluating the impacts of policies and projects that result in a change in emissions and quantifying the economic impact of that change. New York released an report outlining their damages-based approach for valuing carbon, which generally followed a process and method established by the U.S. Interagency Working Group.

Evaluating Additional Health Cost Impacts

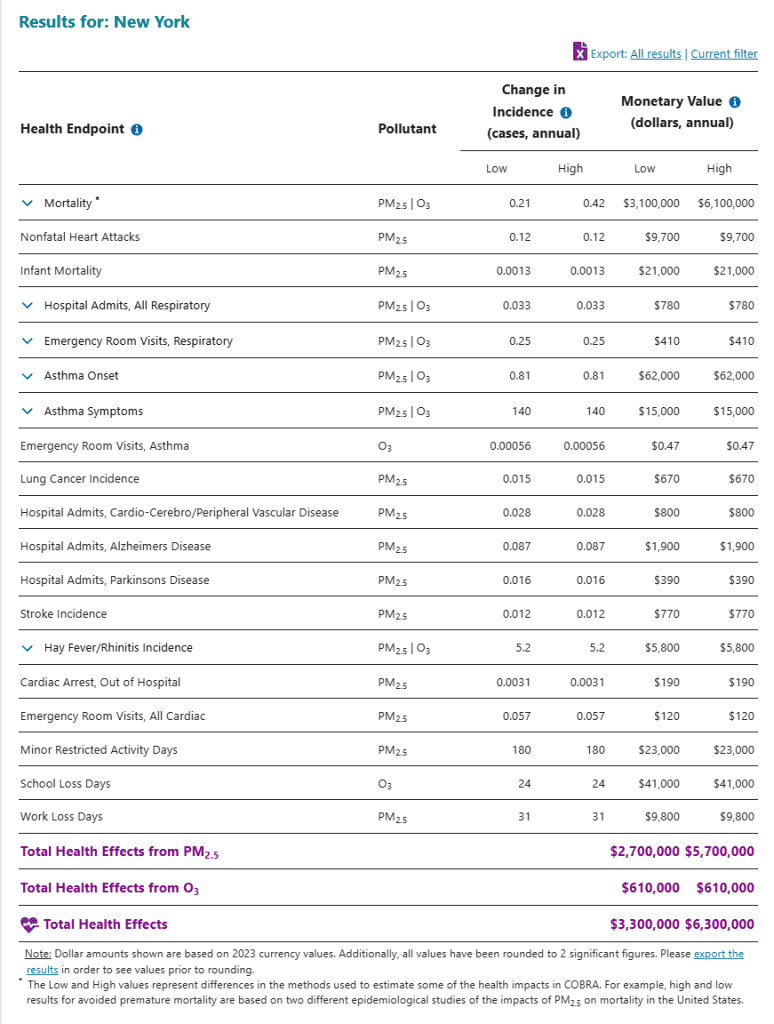

While this social cost of carbon approach addresses GHG pollutants (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, sulfur hexafluoride, and some HFCs), New York’s buildings are also responsible for emitting Clean Air Act regulated criteria pollutants such as VOC, NOx, SO2, and PM2.5, which have demonstrated and measurable adverse health effects. These health impacts are distinct from those considered under the social cost impact models which only evaluate health costs attributable to climate change (such as heat- and cold-related mortality risks). To evaluate health cost impacts associated with criteria pollutants from various sectors, the EPA has developed a separate modeling tool called the Co-Benefits and Risk Analysis Tool, or EPA COBRA tool.

EPA Co-Benefits and Risk Analysis Tool Results – New York State Residential On-Site Combustion

Combustion equipment, such as oil and gas fired furnaces and boilers, directly emit these criteria pollutants, while electric equipment is indirectly responsible for emissions due to emissions associated with electricity generated from fuel combustion.

This ASHRAE paper details an NBI study examining two code scenarios in New York: adoption of the 2024 IECC model code and adoption of zero emission advanced energy code. We evaluated the energy and emissions associated with the two code scenarios, and compared energy cost savings, social cost of carbon impacts, and health cost impacts. Our findings indicated that social cost savings associated with the advanced energy code scenario totaled up to over half of the energy cost savings. New York’s low and high end estimated health cost savings associated with the advanced energy code were 24% and 46% of the energy cost savings respectively. The study also evaluated if increases in electricity use (due to buildings switching from fuel-fired equipment to electric equipment) might increase grid generated emissions and lead to adverse health impacts on communities around point source grid generation plants. The findings indicated that emissions from the grid and its associated health costs increases were very small compared to the health cost savings associated with reducing on-site combustion.

This graph summarizes the estimated cost impacts related to the energy code scenarios evaluated in our study. It shows cumulative values for health costs that would be avoided from onsite emissions reductions, energy cost savings, social cost of carbon savings, and health cost increases associated with increased electricity grid emissions. Our findings indicated that New York’s annual health cost savings associated with the advanced energy code were not insignificant when compared to the annual energy cost savings.

This graph summarizes the estimated cost impacts related to the energy code scenarios evaluated in our study. It shows cumulative values for health costs that would be avoided from onsite emissions reductions, energy cost savings, social cost of carbon savings, and health cost increases associated with increased electricity grid emissions. Our findings indicated that New York’s annual health cost savings associated with the advanced energy code were not insignificant when compared to the annual energy cost savings.

Implications for Developing Future Energy Codes

The findings regarding health cost impacts of energy codes have important implications for national model code and state and local code development and adoption processes. How do we optimize the health and safety objectives for governing jurisdictions adopting and modifying the national model codes? How should they modify the cost effectiveness evaluations that are integral to rulemaking and adoption decision making processes?

More and more studies are concluding that criteria pollutants from buildings are increasingly important to public health as power production and vehicular travel becomes cleaner. Because of heat pumps, electrification of building thermal loads is becoming a low-hanging fruit for improving the air quality and reducing public health impacts in America. Our paper demonstrates that air pollution-related health costs and social cost of carbon combined can exceed energy cost savings attributable to national and local energy codes. The social cost of carbon and health impacts from criteria pollution can and should be considered in all future cost-effectiveness evaluations of energy codes. NBI staff are engaged in evaluating opportunities for incorporating these findings into our code proposals—please join us in helping energy codes be most effective for meeting national and local policy priorities.

Authors

Co-authored by Tristan Grant, Associate Director of Codes and Policy, New Buildings Institute

Bio

Co-authored by Jim Edelson, Senior Climate Advisor, New Buildings Institute

Co-authored by Jim Edelson, Senior Climate Advisor, New Buildings Institute

Co-authored by Grant Sheely, Technical Associate, New Buildings Institute

Co-authored by Grant Sheely, Technical Associate, New Buildings Institute

Did you enjoy this content? Consider supporting NBI’s work with a donation today.