A steamy hot water shower to kick-start or end a long day is a comforting aspect of our everyday lives. But what do you really know about all the hot water traveling through our pipes and faucets?

There’s a fascinating history filled with discovery and the quest for innovation.

Are you thinking of rooms packed with bubbling experiments, groundbreaking innovations, bumps, and failures? If so, you’re on the right track because all that, and more, led to the most efficient water heating technology ever created—the heat pump water heater (HPWH).

The story of heat pump-powered hot water dates back centuries and began with a freezing twist. The quest for knowledge started not with the search for heat but for something cold. Before we delve into the story of artificial heating, let’s examine the events and timeline that paved the way for water heating, which began with early refrigeration methods.

Let’s Go Back in Time! The Names Who Brought Us Here

Once upon a time, in 1748, William Cullen was spending his days toying with the innovation of a small refrigerator machine. Working in the United Kingdom, he used a pump to create a partial vacuum in a container filled with diethyl ether, lowering its boiling point and causing it to boil, thereby capturing heat from the surroundings. This led to the formation of small quantities of ice.

Although this invention didn’t succeed commercially, it still planted the seed of heat pump technology that would revolutionize the water heating industry centuries later. William Cullen’s innovation sparked curiosity and captured the attention of Benjamin Franklin and John Hadley, who further explored and stumbled upon another fascinating discovery: the evaporation of volatile liquids under certain conditions led to draining heat from the surrounding air.

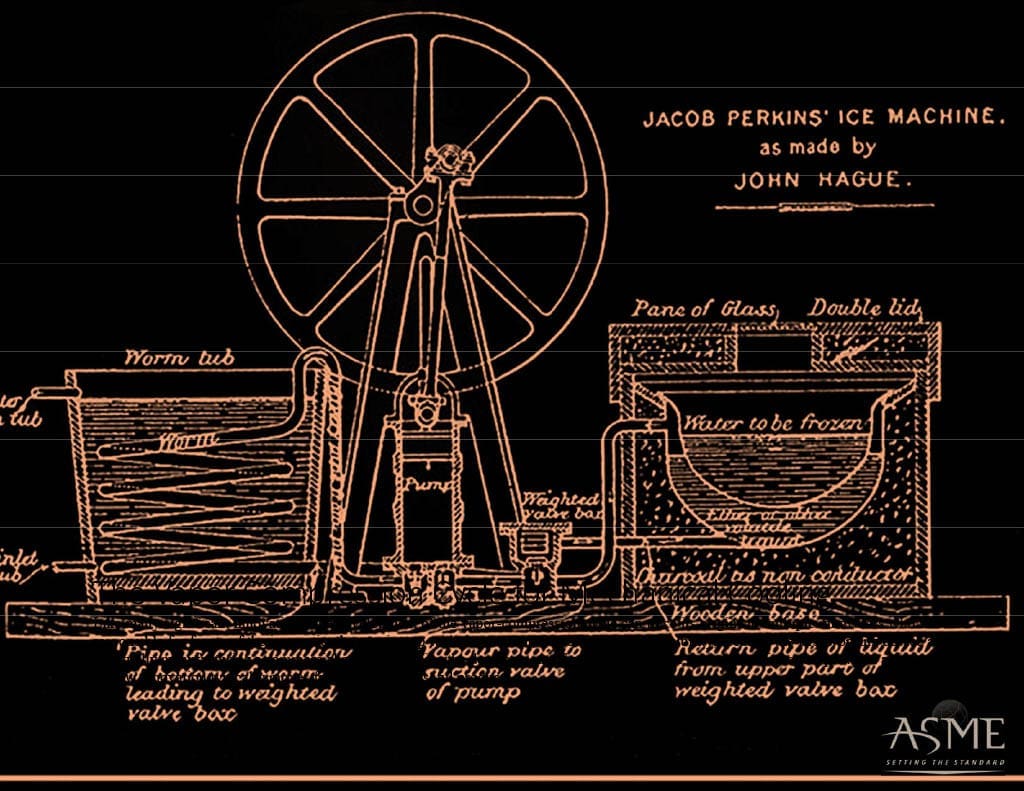

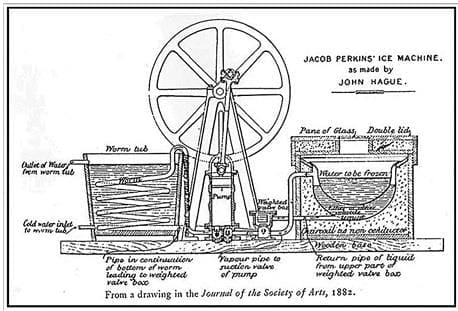

This discovery led others to take a leap of faith, and a few decades later, Jacob Perkins (1834) took this early concept a step further. He transformed the theory by building the first vapor compression refrigeration system.

Jacob Perkins’ “Ice Machine” — American Society of Mechanical Engineers

Jacob Perkins’ “Ice Machine” — American Society of Mechanical Engineers

These frozen (commercial) failures of artificial refrigeration experiments laid the groundwork for the concept of heat transfer with heat pumps. Around 1852, Lord Kelvin explored thermodynamics, laying the groundwork for the principles of heat pump technology in space heating. He suggested using mechanical energy to absorb heat from cooler places and transfer it to warmer ones.

A few years later, from 1885 to 1887, Peter Von Rittinger quickly put this theoretical blueprint to practical use. In a separate part of Europe, in Austria, Peter Von Rittinger built what’s considered the first heat pump system while experimenting with harnessing the latent heat energy of water vapor to evaporate brine in salt marshes. Later, in 1928, his concept was assessed for space heating via a water source system in Geneva.

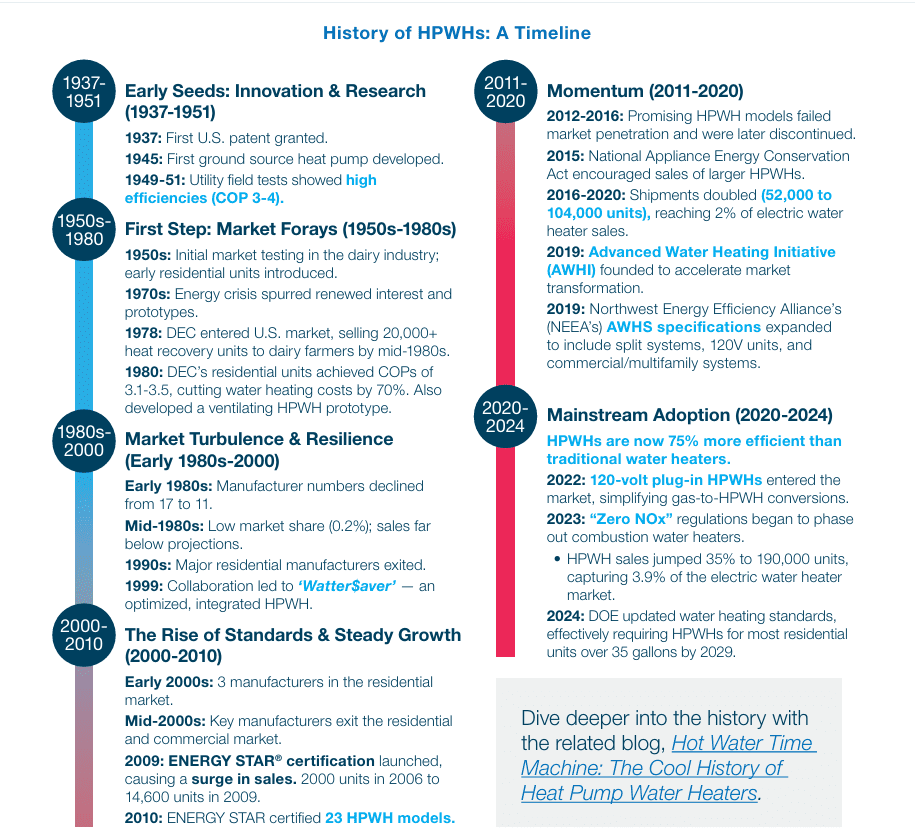

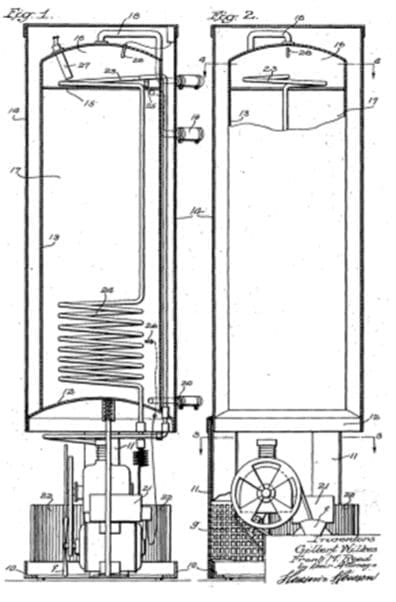

Rumbling into the 20th century, scientists moved from simply exploring the science and technology of heat pumps to building and patented them. T.G.N. Haldane was likely the torchbearer who patented his invention of the heat pump system used for both heating and cooling with a vapor compression cycle in Scotland in the years 1927-1928. Following closely behind, Wilkes and Reed (1937) registered the first patent for a heat pump system in the U.S.

1st U.S. Patent for HPWH—Wilkes and Reed 1937

1st U.S. Patent for HPWH—Wilkes and Reed 1937

The Rise of the First HPWHs—1945 – 1950

Post World War II, heat pump technology innovation accelerated across the U.S. and the U.K. In 1945, John Summer in Norwich (U.K.) developed the first large-scale heat pump system. However, not all successful innovations find their footing on their first attempt. Despite this heat pump’s efficiency and effectiveness, the market was still dominated by low-cost equipment using affordable coal and natural gas sources.

Across the other side of the U.S., around the same time, in 1945, an American inventor, Robert C. Webber, had his moment. Webber was an Indianapolis Power and Light Co. employee with a keen eye and a deep freezer at the time. Robert was experimenting with his deep freezer to effectively store meat for more extended periods without it spoiling. During this experiment, he touched the outlet pipe, and as he did so, he realized that heat was expelled from the freezer, almost burning his hand.

He understood that the freezer was not losing heat but moving heat outside—he effectively capitalized on this waste heat. He used it for water heating by connecting the outlet pipe to a water boiler, and also utilized the dissipated heat for space heating. The positive results and insight ultimately led to the invention of the first functioning ground-source heat pump.

Catching Stride—1950 – 1980

By 1950, the nascent technology of Heat Pump Water Heaters was no longer a mere theory or an accidental discovery. This new technology began to capture the attention of manufacturers and researchers as an emerging solution for water heating.

The 1950s proved to be a significant decade for HPWHs. Some studies suggested the seeds of HPWHs sprouted in the central and eastern U.S. market around the early 1950s. Some credit Hotpoint (later a division of GE) & Harvey-Whipple Company for introducing the first mass-market of HPWHs1,2.

During this period (1950-1980), the inventions, innovations, and patents received additional support from utilities and the National Rural Electric Cooperatives Association (NRECA). The utility industry’s “Heat Pump Water Heater Steering Committee” even conducted field testing of about 30 units in the early 1950s, and NRECA carried out similar testing in the 1970s2. The energy crisis of the 1970s proved to be a driving force, helping to renew interest in HPWHs. NRECA and DOE developed a HPWH prototype and produced 100 units for field testing conducted by 20 utilities.

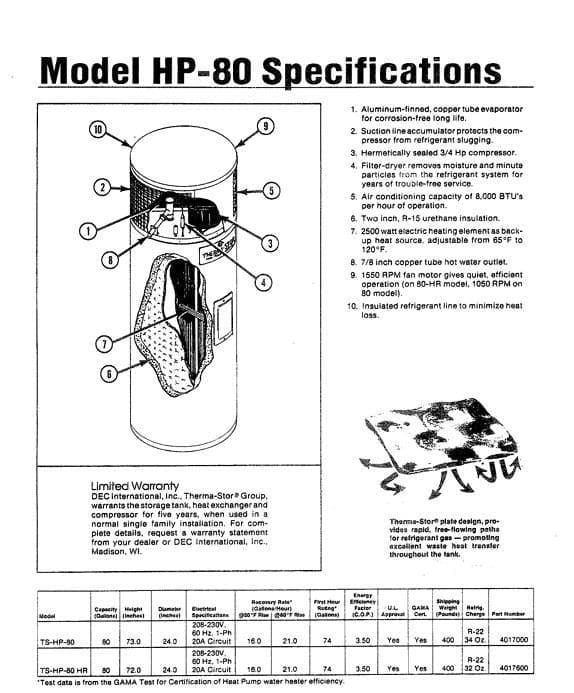

One of the refrigerant water heating units, AKA, HPWH, created in the U.S. — Kenneth Gehring

One of the refrigerant water heating units, AKA, HPWH, created in the U.S. — Kenneth Gehring

Additionally, the Dairy Equipment Corporation (DEC) International entered the heat pump water heater (HPWH) market with a “Heat Transfer Concept and a Refrigerant Heat Recovery Unit.” This concept was initially developed for the dairy industry’s constant need for heating and refrigeration. After initial testing of the first product line, their glass-lined storage tank encased with a waffle heat exchanger proved highly successful in the dairy farming industry, accounting for about 90% of units sold to dairy farmers and resulting in over 20,000 installations (by the mid-1980s). This success led to the establishment of Therma-Stor Products Group, which aimed to adapt and further evolve this efficient heat transfer technology for non-agricultural consumers. It soon became standard equipment in supermarkets and restaurants, earning design and energy conservation awards. Therma-stor’s residential HPWH units, developed in 1980 and tested according to DOE standards, achieved a COP of 3.1-3.5, reducing water heating costs by 70%. They also developed a 52-gallon, 100 CFM prototype (HPV-52) of a ventilating HPWH.

Market Setbacks – 1980-2008: Twin Struggles of Residential and Commercial HPWHs

The promising results of testing in the 1970s carried the hope of HPWHs into the 1980s, with 17 manufacturers entering the market. But every good story goes through a series of twists and turns. By the end of the decade, 17 manufacturers had dwindled to three3. The market share plummeted dramatically to a meager 0.2%, with annual sales of 11,000 units. The decline continued in the 1990s, with prominent manufacturers like Rheem and State quietly exiting the HPWH market. By 1990, with only two manufacturers, HPWH sales dropped from 10,000 units to a low point of 2000 units sold. The turn of the century saw attempts to revive the moribund HPWH market.

In 1999, a collaborative effort between the California Energy Commission (CEC), NYSERDA, and ECR International led to the development of the ‘Watter$aver’ product. The WatterSaver™ HPWH was an early stand-alone heat pump water heater evaluated in a 2002 study by Steven Winter Associates in partnership with Connecticut Light & Power. The study observed an average effective Coefficient of Performance (COP) of 1.67. Although customer satisfaction was generally positive, with feedback on the benefits of dehumidification, there were consistent issues, including excessively hot water (sometimes exceeding 150°F due to tank stratification) and frequent shutdowns caused by high-temperature safety switches. The product ultimately exited the market due to these performance problems and a lack of service infrastructure. Then, in 2003, the DOE funded a project for Carrier’s CO2 refrigerant (R744), which developed 13 prototypes but reportedly failed in commercialization4.

The setbacks continued into the early 2000s, with some manufacturers, such as Bosch, Electrolux, GE, and Westinghouse, exiting the market due to discontinued HPWH models. At this point, the HPWH market had only one manufacturer making integrated units. Two others were making add-on units, i.e., HPWHs that connect to an existing water heater tank. However, these efforts ultimately proved unsuccessful in the long run. Furthermore, the housing market collapse of 2006-07 added to the tide of market disappointments.

United in Struggle: Commercial HPWH Market

The uncertainty and market fluctuations were not limited to the residential sector alone—similar disruptions were also felt in the Commercial HPWH market. Swimming pools are another application area for commercial HPWHs. But despite this sector having decent coverage across homes and hotels, the number of manufacturers declined—from 13 in 19896 to about five by 20097.

Following the footsteps of the residential market, some early studies reported that commercial HPWHs became available in the market around the 1960s. However, unlike the residential segment, there is limited documentation available to depict the state of the commercial HPWH market between 1960 and 1990. During the 1990s, the market saw annual sales of approximately 2,000 to 4,000 units, supported by over 14 manufacturers. However, this stable market crumbled in the following decade. By 2002, only two manufacturers remained5 and sales dropped below 1,000 units.

Outside of the market fluctuations, there were some positive interventions. The 1990s saw several successful field tests. One such test led to installing 45 units in restaurants and laundromats, with reported payback periods ranging from 9 months to 5 years8.

HPWH Revival – 2009 – 2020

But as the saying goes, every cloud has a silver lining. After decades of uncertainty, the HPWH story finally had a turning point with the intervention of ENERGY STAR® in 2009. ENERGY STAR® first certified HPWHs as an energy-efficient product that year, and this was enough to breathe new life into this product category. According to an early ENERGY STAR® report9 , sales increased from 2000 (2006) to 14,600 units (2009), and the number of certified HPWH models skyrocketed to 23 by 2010. Around the same time (2009), DOE invested in further development, such as CO2 HPWH development with GE, with an anticipated completion in 2015. Although GE didn’t launch HPWH with CO2 refrigerant, they introduced the first generation ‘GeoSprings’ series (later expanding to 8 models) in 2012. During this time, many stakeholders began to recognize the importance of HPWHs and joined forces to promote their adoption. The National Appliance Energy Conservation Act of 2015 boosted the sale of HPWHs.